Blog Home

| Image | Title | Full Text | Categories | Date | hf:categories | hf:tags | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

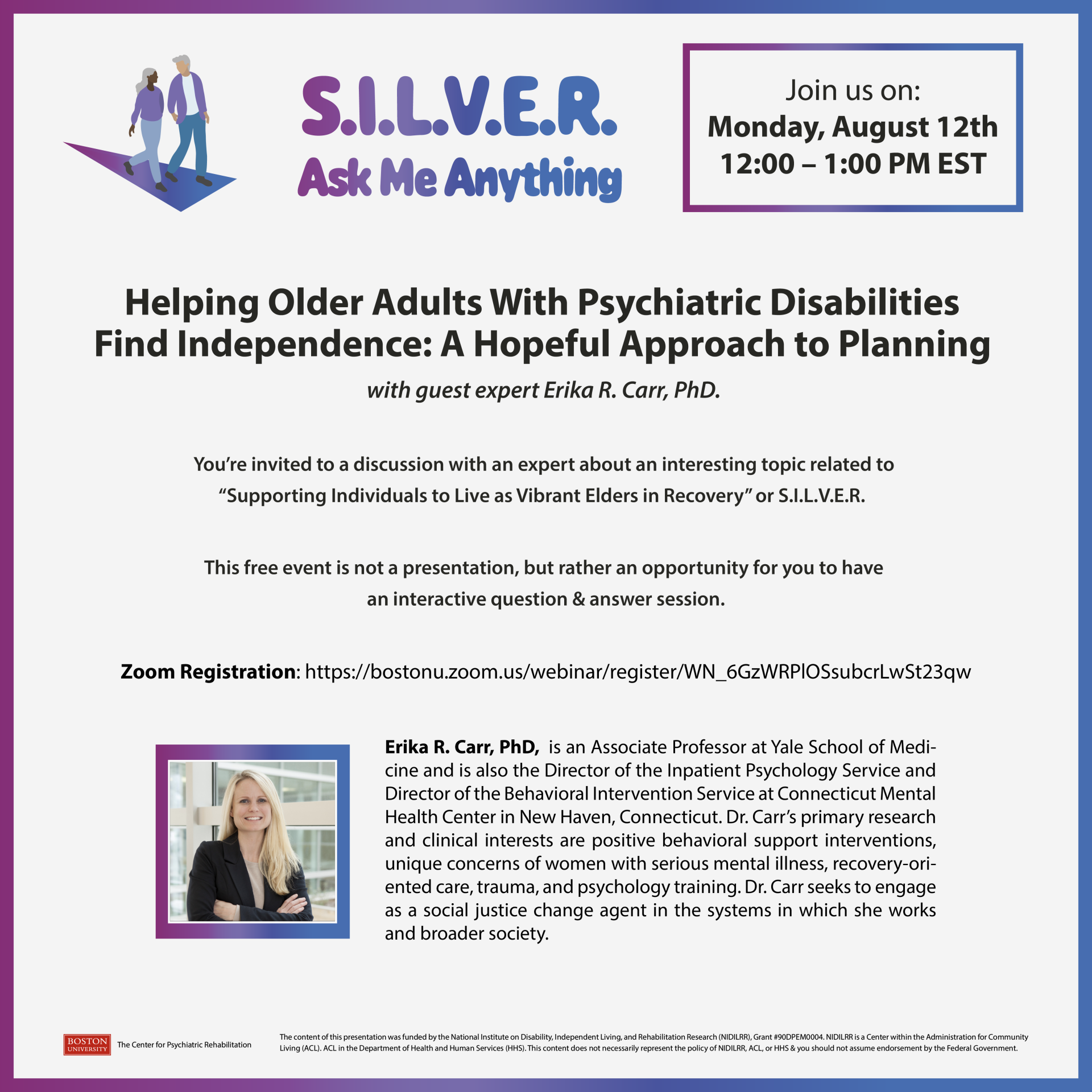

| S.I.L.V.E.R. Ask Me Anything w/ Erika R. Carr, PhD (Aug. 12th, 2024) – Helping Older Adults with Psychiatric Disabilities |

Register here.

| Healthy Aging (S.I.L.V.E.R.) | July 24, 2024 | healthy-aging-silver | psychiatric-rehabilitation serious-mental-illness silver-ama-aging webinar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Making Sense of S.I.L.V.E.R. Research w/ Michelle Zechner, PhD (Jul. 17th, 2024) – Old Before Their Time |

This event has passed. View the recording in our archives, here.

Notice: This event is funded under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RTHF0007). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The statements made during the event do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. | Events, Healthy Aging (S.I.L.V.E.R.) | July 17, 2024 | events healthy-aging-silver | mssr serious-mental-illness webinar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

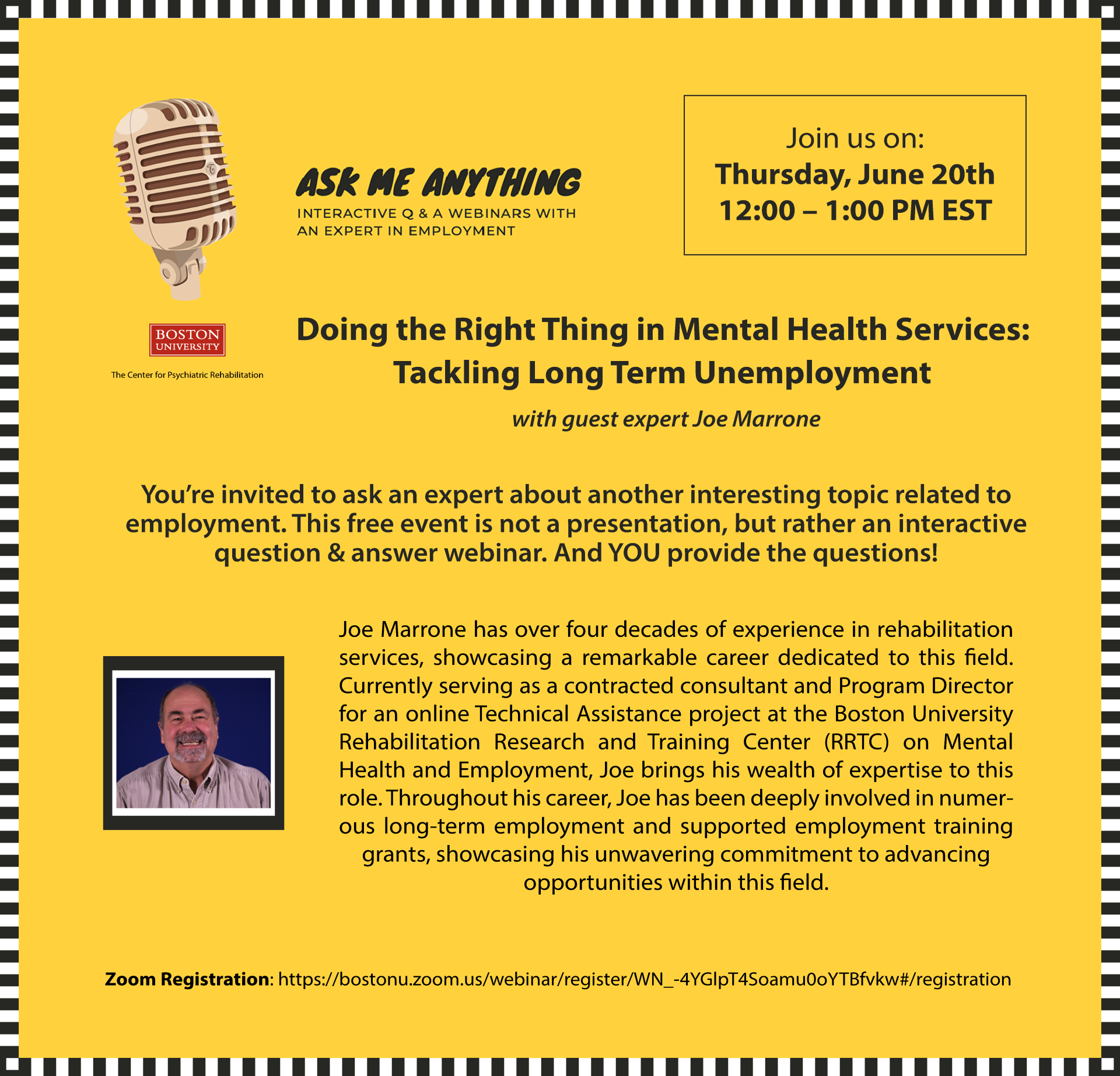

| Ask Me Anything About Employment w/ Joe Marrone (Jun. 20th 2024) – Doing the Right Thing in Mental Health Services: Tackling Long Term Unemployment |

This event has passed. View the recording in our archives.

Notice: The contents of this post were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RTEM0004). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this post do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. | Employment, Events | June 24, 2024 | employment events | ama-employment unemployment webinar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| New MSER w/ Dr. Uma Chandrika Millner (May 16th, 2024) – Thriving at Work While Living with Mental Illness | The Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation is pleased to present “Making Sense of Employment Research”, a webinar series designed to discuss a recent published research study, in a clear and relevant way, even for those who know little or nothing about research. This interactive webinar will highlight the conditions necessary for thriving at work among individuals living in challenging mental health situations. We will emphasize fairness as the foundation to thriving and the importance of (re)storying multiple perspectives, centering decent work as a basic human right, and identifying the psychological, social, and structural systems necessary for thriving. We will highlight the specific needs of Black, Indigenous, and Other People of Color (BIPOC) and Transgender individuals with lived experience. Dr. Uma Chandrika Millner (she/her) is an Associate Professor in the Department of Psychology and Applied Therapies at Lesley University and part-time faculty at Boston College. Prior to Lesley, she worked as a Research Scientist at Boston University. Her overall professional approach is grounded in anti-colonial frameworks and intersectionality. Dr. Millner’s research focuses on work and wellness for marginalized and minoritized communities including individuals with psychiatric disabilities and Asian Americans. Dr. Millner has conducted numerous research projects involving qualitative and quantitative methodologies focused on community integration of adults with psychiatric disabilities.

This event has passed. View the archived recording, here.

Notice: The contents of this post were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RTEM0004). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this post do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. | Employment, Events | April 24, 2024 | employment events | mser-employment psychiatric-rehabilitation serious-mental-illness webinar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MSSR w/ Nathaniel A. Dell, Ph.D. (Apr. 11th, 2024) – Promoting Recovery Among Older Adults with Serious Mental Health Conditions: Strategies for Implementing Psychosocial Interventions in Community Mental Health Settings |

This event has passed. View the recording in our archives, here.

Notice: This event is funded under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RTHF0007). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The statements made during the event do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. | Events, Healthy Aging (S.I.L.V.E.R.) | March 21, 2024 | events healthy-aging-silver | mssr psychiatric-rehabilitation serious-mental-illness | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SILVER AMA w/ Dr. Laura Leone, Lyn Legere, and Karen Gross (Mar. 22nd, 2024) – Forging a Resilient Alliance to Promote Connectedness Among Older Adults with a Psychiatric Disability |

This event has passed, view the recording in our archives, here.

Notice: This event is funded under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RTHF0007). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The statements made during the event do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. | Events, Healthy Aging (S.I.L.V.E.R.) | March 19, 2024 | events healthy-aging-silver | psychiatric-rehabilitation serious-mental-illness silver-ama-aging | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| State of the Science: Supporting Elders to Live as Vibrant Elders in Recovery (S.I.L.V.E.R.) | Steve Bartels MD, MS It is my distinct privilege to provide this inaugural commentary as the Senior Scientist for the recently funded Rehabilitation Research and Training Center “Supporting Individuals to Live as Vibrant Elders in Recovery” (S.I.L.V.E.R. RTCC) at the Boston University Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation. The 5-year S.I.L.V.E.R. RRTC is funded by the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR), Administration for Community Living, HHS and under the direction of Drs. Marianne Farkas and Zlatka Russinova of the Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation at Boston University.

Over the past three decades I have been involved in research with a research team including researchers on the S.I.L.V.E.R. RRTC ( i.e., Sarah Pratt and Kim Mueser) focused on the growing numbers of older adults with serious mental health challenges. What have we learned? First, with the aging of the baby boomer population, the numbers of individuals who are over the age of 60 with serious mental health challenges has been dramatically increasing. However, this increase is qualified by a dramatic health disparity for middle-aged and older adults with mental health diagnoses such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. This health disparity is manifested in a 20 to 30-year reduced life expectancy, largely due to high rates of health-related conditions such as obesity, tobacco use, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer. In addition, people with serious mental health challenges between the ages of 50 and 65 are three and one-half times more likely to be admitted to a nursing home, despite most individuals preferring to live independently in the community.

The United States Supreme Court “Olmstead Decision” interpreted the Americans for Disability Act (ADA) as a directive that individuals who prefer to live in the community with a disability should have that choice. Tragically we have not delivered on that mandate. There are many reasons for this shortfall, including a lack of affordable housing, a lack of appropriate community-based mental health and physical health care services, and a lack of rehabilitative and support services tailored to meet the special needs of older adults with mental health challenges living in the community. Of note, this shortfall in services is not due to a lack of research on evidence-based practices. We know what works, but evidence-based practices have not been adopted by state mental health authorities or broadly implemented. There is a small, but significant body of research on effective psychosocial interventions and treatments for older adults with serious mental health challenges. To provide guidance, I was pleased to lead the development of an evidence based resource guide for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA) titled “Psychosocial Interventions for Older Adults with Serious Mental Illness” that is now featured in SAMHSA’s Evidence Based Resource Guide Series

(https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/pep21-06-05-001.pdf). This review provided detailed descriptions of five evidence-based psychosocial interventions with proven effectiveness, including two developed by our research team: Integrated Illness Management and Recovery, and Helping Older People Experience Success or “HOPES.” With the newly funded center, S.I.L.V.E.R. researchers are engaged in building on what we have learned in prior research to develop and test exciting new interventions and programs over the coming years.

Among the most pressing impediments to advancing mental health access is a substantial shortfall in the trained workforce. I also had the recent privilege of participating in a National Academy of Medicine workshop on this topic titled “Addressing the Rising Mental Health Needs of an Aging Population.” This 2024 report provides a valuable overview of data on the incidence and prevalence of mental health conditions in older adults – it describes mental health disparities and the role of social determinants, as well as approaches to improving access and quality of services. This report also provides critical recommendations for addressing the workforce shortfall, and key approaches to advancing supportive communities and future priorities.

As we dedicate efforts to gaining knowledge on optimal approaches to improving services for older adults with serious mental health challenges, there are many high impact opportunities. For example, a team of S.I.L.V.E.R. researchers is currently engaged in a multi-state project to determine the status of dedicated state plans and policies for older adults with serious mental health needs. Other opportunities include modifying and adapting the proven evidence-based practices to improve broad uptake, implementation, spread, and sustainability. These efforts will benefit from considering health equity as a major goal and understanding factors contributing to physical and mental health disparities. The Knowledge Translation team at the S.I.L.V.E.R. RRTC will be contributing to determining the most promising approaches to developing a trained workforce prepared to address the needs and preferences of older adults with serious mental health challenges and the policy initiatives necessary to achieve effective service delivery for this important and rapidly growing population. I am excited by the amazing opportunity provided through funding from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR) supporting the newly funded S.I.L.V.E.R. RRTC. I look forward to working with our extraordinary team to make a difference in the lives of older people with mental health challenges. Details on many of these efforts will be featured in future blogs. Stay tuned! Dr. Bartels is Senior Scientist for “Supporting Individuals to Live as Vibrant Elders in Recovery (SILVER RRTC) and the James J. and Jean H. Mongan Chair in Health Policy and Community Health, Director of Mongan Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School.

Notice: The contents of this post were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RTHF0007). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this post do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

| Articles, Healthy Aging (S.I.L.V.E.R.) | March 4, 2024 | articles healthy-aging-silver | psychiatric-rehabilitation serious-mental-illness | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reclaiming Peer Support: Make Your Credential Work For You |

March 4th, 2024

A vast majority (90%) of the public agrees that there is a mental health crisis in the United States. The causes of this collective crisis are numerous, but regardless of where you live or work, you likely know someone who has struggled to get the support they need for emotional distress, drug use, or despair. Maybe you have been that person. Over the past three decades, and around the country, peer support specialists (sometimes called peer supporters, certified peer specialists, or simply “peers”) have entered mental health service agency’s workforce. While each state has its own training and credentialing process, all peer support specialists have personal experience of mental health or substance use challenges – including depression, thoughts of suicide, drinking or drug use, hearing voices, autism, and in some cases may be family members.

Unlike mutual support groups (such as AA, which is run by volunteers), peer support specialists are paid professionals who receive training to use their lived experience to help others. Peer support means connecting with others who are struggling with similar issues by relating as a compassionate equal and empowering them to choose their own path to recovery. It has a positive impact on both service users and the peer support specialist. Peer support specialists pursue this line of work because they want to give back and help others. They are generally satisfied with their jobs, making it an appealing career opportunity. However, they also face barriers that other healthcare professionals do not. Many peer support specialists say that they don’t have enough prospects for career advancement. Compared to other healthcare workers performing similar jobs, they are paid relatively low wages ($15-18/hour), struggle to find jobs, and often lack financial security. We hear from peer support specialists that coworkers don’t respect their work or understand their role, and it may be difficult to obtain disability accommodations. Disparities are particularly problematic for women and BIPOC individuals.

Our research has found that about 30% of credentialed peer support specialists want to develop a business to support in their community. Those who were interested in self-employment were more likely to have experienced negative workplace dynamics. Being self-employed in your own private practice means that you can have more flexibility in the hours you work, the customers you choose to work with, and the way you do your job. It may also mean earning a higher wage and more job security, which we hope to research in the future. Peer support businesses can expand and improve services for community members who want more choices in their treatment. In fact, our research found that in areas where there are not enough mental health providers, peer support specialists were more likely to stay in the field rather than leave for other opportunities. This means that peer support specialists may be able to fill some gaps in healthcare provider shortage areas. If peer support services were more readily available it could improve access to services, and create better working conditions. A win-win. Other healthcare providers are empowered by the law to open private practices but there is no designated avenue for private peer support practices. Credentialing and training of peer specialists, unlike other practitioners such as psychologists and social workers, typically occurs through a state entity, may vary widely in quality standards, and is not necessarily administered by a professional association or credentialing entity. This means there is no licensing process, which is typically the first step to practicing independently. There is no formal infrastructure or guidance for peer support specialists who want to start a practice business, and a lack of understanding of how jurisdictional liability and health insurance would apply to such a practice. They may face challenges such as how to bill Medicaid, receive required supervision, get professional liability insurance, and manage finances. It isn’t even certain that a peer specialist can move states and qualify for the new state’s certification. Nonetheless, peer support specialists are forging the path towards independent practice, such as through online platforms such as HeyPeers.com.

Starting a business is hard work, and often doesn’t pay off for a few years. It is extra hard to start a new type of business, built upon an innovative idea, particularly when you have struggled with poverty, disability, long-term unemployment, and discrimination. There are freely available resources in every community to help people start a business (such as SCORE or the Small Business Development Center), but often these services are not designed to help people with mental health challenges around work, or they simply aren’t knowledgeable about peer support services and the requirements of the job. If you are on Social Security benefits, there is also support such as the Plan for Achieving Self-Sufficiency (PASS) or vocational rehabilitation, but services from the Department of Rehabilitation are not always geared to help people start a business.

Because of my love for owning my business and wanting to help the peer community, my team created Reclaiming EmploymentTM. The program offers self-employment education and a community of support for people with mental health-related challenges around work. In preliminary research, Reclaiming Employment has been shown to improve feelings of self-efficacy around entrepreneurship – the feeling that I can do this. This summer we’ll be launching a new cohort of users that may also receive one-to-one and group coaching from a peer support specialist. If you’re interested in being a part of our community, please email info@reclaimingemployment.com and let us know to extend an invitation!

Notice: The contents of this post were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RTEM0004). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this post do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. | Articles, Employment | March 4, 2024 | articles employment | peer-support psychiatric-rehabilitation serious-mental-illness | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AMA w/ Dr. Anneliese de Wet (Feb. 16th, 2024) – Stigma & Stigma Resistance… the #1 Reason for Peer Worker Turnover |

This event has passed. View the recording in our archives here.

Notice: This event is funded under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RTEM0004). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The statements made during the event do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. | Employment, Events | February 8, 2024 | employment events | ama-employment peer-support webinar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| College Mental Health Education Programs: Accessing Facilitation Guides, Curriculum, and Support (Jan. 23rd, 2024) |

Boston University Sargent College of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation COLLEGE MENTAL HEALTH EDUCATION PROGRAMS: ACCESSING FACILITATION GUIDES, CURRICULUM, AND SUPPORT Join us JANUARY 23, 2024 – 2:00pm-3:00pm The College Mental Health Education Programs (CMHEP) team at Boston University has partnered with colleges, universities, and organizations across the United States and internationally to successfully adapt and adopt several curricula designed to support college students facing mental health challenges during their higher education journey. CMHEP provides structured lesson plans that are tailored to the unique needs of schools and organizations, offering detailed facilitation guides, workshops, and support. Their programs combine wellness and resiliency skill building with academic instruction and coaching, delivered as in-person or distance learning opportunities, to help students who are struggling on campus to thrive. In this webinar, presenters will share details of three specific, open-access programs designed to help students facing mental health challenges. Participants will be encouraged to rethink how we deliver college mental health services to include recovery and rehabilitation interventions that can support students with mental health conditions to remain in, return to college, and develop new strategies to alleviate the burden on staff.

Presenters:

Chelsea Cobb, LMHC Assistant Director, College Mental Health Education Initiatives

Ali Theis, LICSW Senior Training Associate, College Mental Health Education Programs

| Other | January 19, 2024 | other | cmhep | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MSER with Dr. Marta Elliott, PhD (Jan. 31st, 2024) – Benefits and Challenges of Employment for Individuals Diagnosed with Mental Illness: Qualitative Findings and Ongoing Research |

Notice: This event is funded under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RTEM0004). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The statements made during the event do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. | Employment, Events | January 8, 2024 | employment events | mser psychiatric-rehabilitation serious-mental-illness webinar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| KT Academy / CeKTER Webinar with Marianne Farkas, ScD (Jan. 8th, 2024) – Training Your Staff: What Works? What Doesn’t? |

This event has passed. View the recording in our archives here. | Events, Other | November 24, 2023 | events other | cekter knowledge-translation kt-academy psychiatric-rehabilitation training webinar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MSER with Paul J. Margolies, PhD and I-Chin Chiang, MS (Nov. 15th, 2023) – IPS Supported Employment in the 2020’s: New York State Experience |

This event has passed. View the recording in our archives.

Notice: This event is funded under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RTEM0004). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The statements made during the event do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. | Employment, Events | October 17, 2023 | employment events | mser psychiatric-rehabilitation supported-employment webinar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cognitive Self-Management Strategies for Work and School | by Dr. Susan McGurk and Dr. Kim Mueser

We are constantly barraged in our daily lives with new information competing for our limited attention. And there is even more information available than ever before, at the tip of our fingers, on our cell phones and computers. We need to manage the beckoning alerts of tweets, beeps, pings, and other sounds our devices make to inform us something “important” has happened (such as receiving a cell phone text) or try to be mindful of the accumulation of unanswered messages, posts, and other communications whose arrival we have allowed to go unannounced. Our computers and cell phones are a minefield of emails, prompts, and the bottomless pit of the internet, promising infinite information without protection from the perils of endless distractions. Even the mere presence of your (turned-off) cell phone can drain your attention. It is not surprising then, that we often end our day feeling mentally exhausted but without completing the tasks that we need to get done.

Although attention is a keystone thinking skill and a precious, limited resource for managing information, it is just one of several cognitive domains that serve us in our day-to-day lives. We also need to learn and remember information, plan ahead, solve problems, and think on our feet. One other often neglected, but critical thinking area is self-thinking. Negative thinking can adversely impact our confidence and effort to achieve what we want to. We need skills to enhance our awareness of such thoughts, challenge them, and replace with them with more optimistic, hopeful, and realistic thoughts. Optimistic thoughts about ourselves and our ability to achieve our daily tasks and reach our long-term goals can fuel the effort that we need to succeed. Proficiency in the full range of areas of cognitive functioning are critical to achieving goals such as returning to school, completing a degree, getting, and keeping work, living independently, making, and keeping friends, and having deep and rewarding relationships.

The good news is that we can sharpen and extend our mental capabilities and maximize our chances of succeeding in any area we choose. We can do all of this by using cognitive self-management strategies. Although some may not be familiar with the term “cognitive self-management strategies,” all of us almost certainly use at least some these strategies in our daily lives. Have you ever:

If so, then you’ve used cognitive self-management strategies. And if you have used one of the above, then you’ve probably used some of the other many possible strategies. While everyone uses cognitive self-management strategies, the more we use the better, and everyone can benefit from learning more strategies or how to use them more efficiently.

We describe below self-management strategies for optimizing and extending thinking skills that can be used in all walks of life. Self-management strategies help us utilize our cognitive skills and the demands on them to maximize their efficiency and effectiveness. Additionally, and perhaps surprisingly, practice and expertise in using these strategies, and incorporating them into our daily routines, further enhances our cognitive abilities in areas such as attention, memory, planning, and flexible (and positive) thinking! Thus, in addition to helping compensate for the cognitive limits everyone has in specific cognitive areas and extending our cognitive reach, practiced use of these strategies can also improve our raw brain power.

Learning and using cognitive self-management strategies can help optimize functioning across a range of daily life activities, such as self-care (such as grooming and hygiene, sleep, managing a medical condition), organizing one’s living space, planning for meals, shopping, connecting with friends or family, work or school, and just plain enjoying life (such as getting out to that movie we’ve been thinking of seeing). For example, common problems such as being late or missing appointments, having difficulty keeping focused on a task, or forgetting instructions or someone’s name can all be prevented by using strategies such as maintaining a personal schedule (and using alarms as needed), removing distractions from one’s environment (such as cell phone or computer alerts), and repeating back/paraphrasing what someone has just said, respectively. Some of these strategies focus primarily on one area of cognitive functioning, such as reducing distractions in one’s environment to improve attention and concentration. Other strategies are helpful for improving the broad range of cognitive performance in daily life (e.g., attention, memory, problem solving), such as developing routines at home, when looking for a job, and at school or work. Because obtaining a job (or getting a promotion at work) or completing a degree or certificate program at school are very common goals for people that have a range of cognitive demands, we address some self-management strategies that are particularly helpful for success in these areas.

The table below contains examples of cognitive areas that are important for work and school, signs of a problem related to each cognitive area, and self-management strategies for addressing (or preventing) each problem

The Thinking Skills for Work* program contains a rich curriculum of cognitive self-management strategies which are incorporated into a series of educational handouts for clients. The self management topics include Cognitive Skills for Work, Recognizing Your Strengths, Challenging Negative Thinking, Improving Attention and Concentrations, Reducing Memory Difficulties, Getting Organized at Home, Getting Organized for Your Job Search, Planning Ahead, Solving Problems, and, Improving Thinking Speed. The handouts provide information about strategies for improving cognitive performance at work in attention and concentration, memory, information processing speed, planning, and solving problems. In addition, several other handouts are devoted to enhancing motivation which can contribute to greater effort and persistence at cognitive tasks, including understanding the relationship between cognitive functioning and work (Cognitive Skills for Work)developing an awareness of one’s personal strengths (Recognizing Your Strengths), and overcoming negative thinking or defeatist thinking that can interfere with getting or keeping a job (Challenging Negative Thinking), (e.g., “No one will ever hire me for a job”). Strategies geared toward successful work are also highly applicable to success in school. The Thinking Skills for Work intervention is a comprehensive program for improving and optimizing your cognitive skills. A comprehensive description of the program can be found at here *SR McGurk, KT Mueser (2021). Cognitive Remediation for Successful Employment and Psychiatric Recovery: The Thinking Skills for Work Program. Guilford Press, New York. Information about the book can be found here.

Notice: The contents of this post were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RTEM0004). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this post do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. | Articles, Employment | October 11, 2023 | articles employment | cognitive-remediation psychiatric-rehabilitation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MSER with Dr. Judith Cook (Sept. 13th, 2023) – Developing a Peer Workforce for Provision of IPS: What Can Research Tell Us? |

This event has passed. View the recording in our archives, here.

Notice: This event is funded under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RTEM0004). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The statements made during the event do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. | Employment, Events | August 28, 2023 | employment events | mser peer-support psychiatric-rehabilitation webinar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

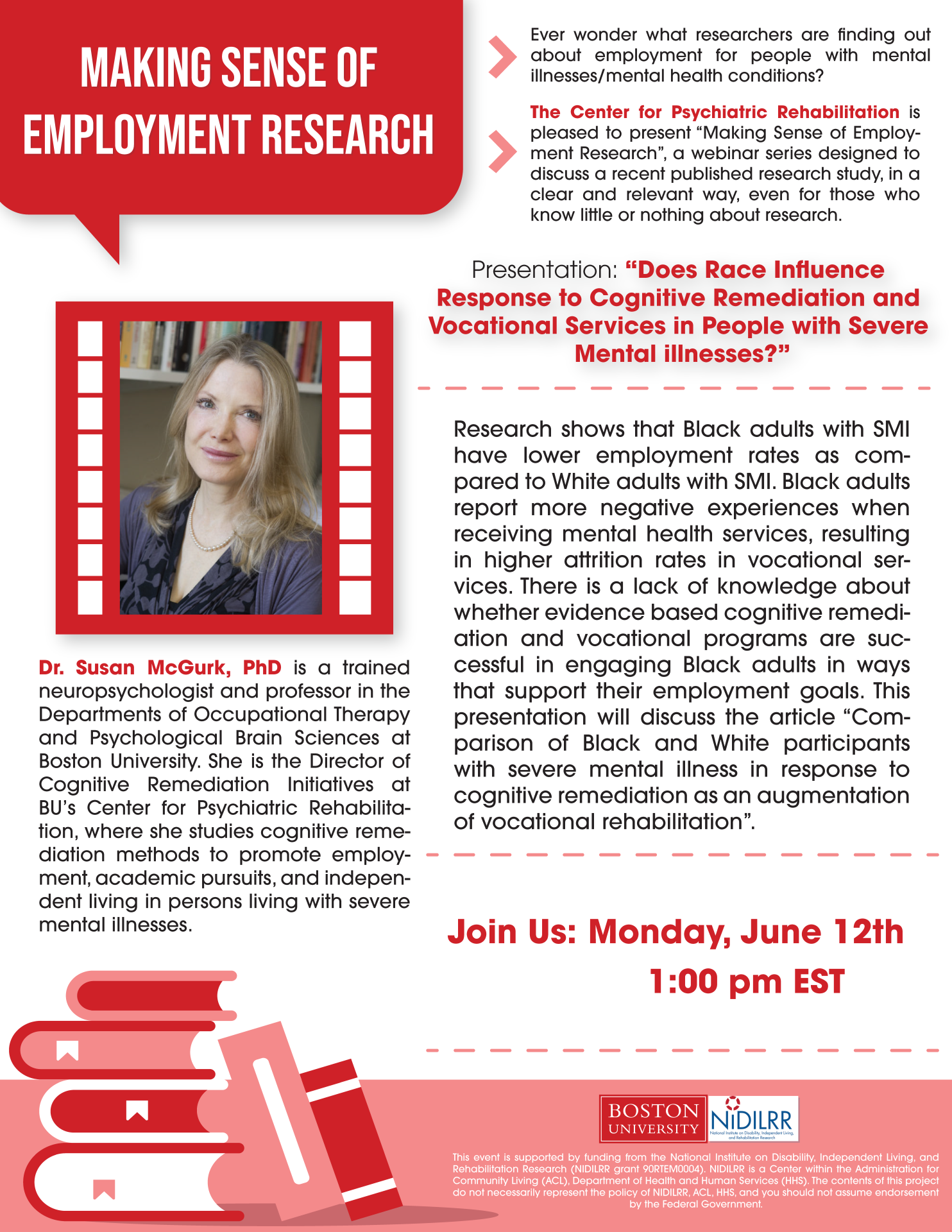

| MSER with Dr. Susan McGurk (June 12th, 2023) – Does Race Influence Response to Cognitive Remediation and Vocational Services in People with Severe Mental Illnesses? |

This event has passed. View the recording in our archives here.

Notice: This event is funded under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RTEM0004). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The statements made during the event do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. | Employment, Events | May 23, 2023 | employment events | mser psychiatric-rehabilitation webinar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AMA Webinar with with Guest Expert Noah Abdenour (May 12th, 2023) – Influencing State Policy Regarding Peer Support |

Influencing State Policy Regarding Peer Support with guest expert Noah Abdenour. ASK ME ANYTHING INTERACTIVE WEBINARS WITH AN EXPERT IN EMPLOYMENT Save the Date: Friday, May 12th 12:00- 1:00 PM EST BOSTON UNIVERSITY You’re invited to ask an expert about another interesting topic related to employment! This free event is not a presentation but rather an interactive question & answer webinar. And YOU provide the questions. Submit webinar questions before the webinar Le MS lynleg@bu.edu’ This event has passed. View the recording in our archives here.

Notice: This event is funded under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RTEM0004). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The statements made during the event do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. | Employment, Events | April 24, 2023 | employment events | ama-employment peer-support psychiatric-rehabilitation webinar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coaching for Peer Specialists | by Sally Rogers and Lyn Legere

The role of peer specialists in behavioral health settings has grown dramatically in the last couple of decades. But, as a relatively new addition to the workforce, it is experiencing “growing pains”. Common experiences relayed by peer support workers include a lack of clarity about how their role fits into the mental health workplace and confusion about what their work tasks should and should not be. For some behavioral healthcare workers, research suggests that this results in stress, distress and burnout, all of which have worsened because of the pandemic (Edú-Valsania, Laguía, & Moriano, 2022; Sklar, Ehrhart, & Aarons, 2021).

The Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation has a long history of collaborating with peer specialists in a variety of ways. In this case, we wanted to support peer workers and were troubled by the usual approaches. We often saw solutions suggesting that the peer worker needed therapeutic intervention or that the job needed to be redesigned to lessen the stress. We found both of these approaches to be objectionable, as they merely reinforced the idea of pathology on the part of the peer worker rather than considering the work setting issues related to integrating a new workforce. Looking at the situation from a workforce perspective, we decided to address this problem with a somewhat novel approach: that of coaching. We know that coaching is an effective tool and has now been applied not only to the sports context, but to lifestyles, wellness, and recovery (Sforzo, et al., 2018; Grover & Furnham, 2016). Most relevant, it has proliferated in work settings, including Executive Coaching. We wondered if Executive Coaching for peer specialists, which keeps the focus squarely on the workplace, might be an effective approach to address work related stressors.

Coaching shares many values of peer support, which makes it very attractive. Some of the advantages of coaching support is that it focuses on establishing a good working relationship and mutual respect, on co-developing goals, and on bringing self-directed strategies to bear to support the person as they strive to reach their goals. However, we wanted to differentiate coaching for peer workers from typical “Executive Coaching” in that we did not want to have any affiliation with the person’s employer. Coachees were free to tell their supervisors about the coaching, should they choose. At the same time, we believed that having a firewall between the employer and the coach gave the peer worker a greater sense of safety to fully share their work situation without fear of reprisal. In 2019, the Center submitted a proposal to develop and research this virtual coaching intervention for peer support workers to the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research, which was funded. To develop the coaching program, we consulted experts in both fields: peer support practice and coaching. We got input from a small group of peer specialists/advocates and also from the Harvard Institute on Coaching (to learn more about coaching from this institute, visit: https://www.instituteofcoaching.org/). Since the coaching would be focused on work issues, it was clear to us that the coaches must have experience as a peer support worker as well as coaching skills. Lyn Legere, herself certified as a life coach and a peer specialist, took the lead on the development of the coaching guide, working with Zlatka Russinova, Director of Research at the Center, and the input of consultants. The peer worker coaching manual consists of several sections providing guidance to coaches. One important section specific to this coaching intervention is “Coaching vs. Peer Support.” The coach’s background in peer support provides knowledge needed to understand challenges that coachees may be experiencing. Here, however, their role is that of a coach. We were very fortunate to have hired two highly experienced peer specialists who were trained to be coaches for this study and who have done an exemplary job. Another important section of the manual is what we called the Topical Guide. This section focuses on areas that we know can be particularly challenging in peer work, including: · Role Overload · Role Confusion/Ambiguity · Work/Life Imbalance · Stigma and Role Devaluation in the Workplace · Dealing with Conflict in the Workplace · Training Gaps or Job Mismatch · It is What it Is: Dealing with Issues Beyond your Control · Wellness Tools for Work Each section has information on the topic as well as tips, strategies and worksheets that can be used in whatever ways seems useful to the coachee.

Of course, funded research has to see how effective any newly developed intervention is. Using surveys, we are trying to learn if the coaching had an effect for people in areas such as role clarity, role confusion, burnout, job satisfaction, organizational climate, job stressors, and turnover intention. Participants complete the survey measures when they first enroll in coaching, and then at the 4, 6 and 9-months mark. Since this study was developed as a randomized trial, only half of the people we enrolled will get the full coaching (designed to be up to 16 weeks long) and the other half are offered one informational session. This will allow us to make good comparisons about the effect of the coaching. Because the project is ongoing, we do not have this data compiled yet, but hope to have some initial outcomes by the endo of 2023. In the meantime, we have also been conducting qualitative interviews with folks who have received coaching. From these interviews, we are learning of the value that participants place on having a knowledgeable peer specialist/coach to discuss their workplace difficulties with, someone who can provide perspective, context, and understanding. Here are some of the things the coachees said: • “Coaching helped humanize my work” • “My coach was a lifeline during a difficult time for me personally” • “I could trust my coach when I hadn’t trusted other providers” • “Coaching was terrific” • “It was lifechanging for me…I learned about myself as a peer and it helped me in my life” • “Personal growth and development—coaching helped me be the best me that I could be and bring that to work’’ • “They listened…” • “Overall, for me, what feels the most helpful, is knowing that when Sunday at 1 comes, there was somebody who gets it, who gets what it’s like to do this work, who gets what it means to have a mental health condition—that alone has been helpful—knowing this carried me through each week” For those interested in learning more about the work of peer specialists, please visit the NAPS website: https://www.peersupportworks.org/ The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration also has information about peer specialists: their role and their competencies. https://www.samhsa.gov/brss-tacs/recovery-support-tools/peers; https://www.samhsa.gov/brss-tacs/recovery-support-tools/peers/core-competencies-peer-workers

If you want additional information about this project, please contact E. Sally Rogers, Project Director at erogers@bu.edu or Lyn Legere, Senior Training Associate at lynleg@bu.edu.

Citations: Edú-Valsania, S., Laguía, A., & Moriano, J. A. (2022). Burnout: A review of theory and measurement. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(3), 1780.

Grover, S., & Furnham, A. (2016). Coaching as a developmental intervention in organisations: A systematic review of its effectiveness and the mechanisms underlying it. PloS One, 11(7). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0159137

Sklar, M., Ehrhart, M. G., & Aarons, G. A. (2021). COVID-related work changes, burnout, and turnover intentions in mental health providers: A moderated mediation analysis. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 44(3), 219.

Sforzo, G. A., Kaye, M. P., Todorova, I., Harenberg, S., Costello, K., Cobus-Kuo, L., . . . Moore, M. (2018). Compendium of the Health and Wellness Coaching Literature. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 12(6), 436-447. doi:10.1177/1559827617708562

Notice: The contents of this post were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RTEM0004). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this post do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. | Articles, Employment | April 13, 2023 | articles employment | coaching peer-support psychiatric-rehabilitation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MSER with Matthew J. Smith, PhD (March 31st, 2023) – Virtual Reality Job Interview Training |

This event has passed. View the recording in our archives here.

Notice: This event is funded under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RTEM0004). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The statements made during the event do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. | Employment, Events | March 15, 2023 | employment events | mser psychiatric-rehabilitation webinar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AMA Webinar with Peer Support Expert Amy Pierce (Feb. 13th, 2023) – Supervising the Peer Workforce in Behavioral Health Settings | Ask Me Anything: Supervising the Peer Workforce in Behavioral Health Settings

You’re invited to ask an expert about another interesting topic related to employment! This free event is not a presentation, but rather an interactive question & answer webinar. And YOU provide the questions. Save the Date: Monday, February 13th at 12:00 – 1:00 PM (Eastern) Ask Me Anything About … Supervising the Peer Workforce in Behavioral Health Settings with guest expert Amy Pierce Amy Pierce, MHPS, PSS, ALF Amy has been working in the peer movement in the State of Texas for almost two decades and now serves as the Recovery Institute Deputy Director. Previously, she was the CEO of Resiliency Unleashed, an international training and consulting company focusing on the development and implementation of peer services. She started the first peer support program in the Texas State hospital system, was a peer support worker in a community mental health agency and served as the Program Coordinator for a transitional peer residential housing project funded through the 1115 waiver program. Amy has held supervisory roles within these programs, developing training for providers across Texas and beyond. Amy is a Mental Health Peer Specialist, a Certified Peer Specialist Supervisor, and trainer/facilitator (Advanced Level Wrap facilitator, ASIST trainer, WHAM facilitator). Amy is a previous chair of the PAIMI council and is a current board member for Disability Rights Texas. Zoom Registration: https://bostonu.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_Tymu99ALReOCUBvV4PFTiA Submit webinar questions before the webinar to Lyn Legere, MS at lynleg@bu.edu Tech Requirements: Accommodation Requests:

This event has passed. View the webinar recording in our archives here.

Notice: This event is funded under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RTEM0004). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The statements made during the event do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. | Employment, Events | January 5, 2023 | employment events | ama-employment peer-support psychiatric-rehabilitation webinar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Online Technical Assistance Model: Action as a Precursor to Knowledge |

The Online Technical Assistance (OTAR) model was developed as a pilot program, with the goal of assisting organizations (e.g. state agencies, providers, for- and non-profit entities) that want to improve their employment outcomes for people with psychiatric disabilities by improving their policies, funding, and system design. Two elements of this are: Program providers perform an assessment of the need for “technical assistance” (TA) services around a specific group of an organization’s [employment focused] goals for the clients or patients it serves. Once the needs of the organization are identified, the consultant develops a site-specific TA plan based on the organization’s response to this assessment. OTAR clarifies a focus on policy and systemic change within participant organizations more than it focuses on training or product development. The model also emphasizes the importance of assigning a subject matter expert (SME) for each organization. Often, it has been advantageous to pursue candidates new to the consulting field with an opportunity to be part of this team and take on this role. The second step is the construction of an implementation team which includes supervisory and clinical management staff as well as relevant partner organization personnel. The OTAR implementation team conducts regular Zoom calls to review the steps included in the plan.

Typically, sites begin their participation through word-of-mouth and email recruitment. Once interest is expressed, potential sites are requested to answer the following simple questions:

Since the project commenced in 10/19, OTAR has worked with several organizations across the country. They have included:

The specific requests for TA varied by site but most incorporated the importance of employment as a core part of Recovery planning in clinical services instead of as a referral point to an employment unit. These included both micro-level discussions on motivating clinical staff to generate interest in employment with their clients and a broader systems-level focus on creating large scale policy and funding models to increase employment outcomes. A few projects related to how to create a system of financial planning advice early in the process for job seekers with disabilities, albeit one short of the more time-consuming full SSA benefits analysis. So, what have we learned?

There are also downsides that have emerged from the online technical assistance model. The initial outreach and engagement with OTAR was presented as a joint priority of each partnering agency with the site’s focus on mental health and employment collaboration. In practice, the commitment to the planned efforts often continued only with some of the participating sites. This most commonly emerges in the context of an employment focused organization getting only intermittent support from the mental health organization (state or local) involved. While the agreement obtained from all sites was to involve at least one of the clinical supervisory and/ or executive level staff, some sites have had only intermittent buy-in from personnel at these levels. Another downside is that site visits are typically used to expand the pool of informants about the local issues supporting or impeding employment. This activity gets lost with distance-TA-only conditions – those in which the consulting team only has direct involvement with the formal coordinating [on-site] group and captures only a limited view of the local environment. Another downside from the consultant perspective is that it is less satisfying and less fun to be unable to connect with local sites in a more personal relationship and to directly observe the impact of the program. It is conceivable that some form of hybrid model could address these issues in the future. For more information about OTAR services contact us at psyrehab@bu.edu.

Notice: The contents of this post were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RTEM0004). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this post do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. | Articles, Employment | December 22, 2022 | articles employment | consulting psychiatric-rehabilitation technical-assistance | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MSER Webinar with Dr. Wallis E. Adams (Dec. 7th, 2022) – The Peer Support Specialist Workforce During Covid-19: Changes, Challenges, and Opportunities |

This event has passed. View the recording and transcript in our archives here.

Notice: This event is funded under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RTEM0004). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The statements made during the event do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. | Employment, Events | November 26, 2022 | employment events | mser peer-support psychiatric-rehabilitation webinar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Two-Part Webinar Series: “The Knowledge to Action Cycle: How Do I Apply it to My Work?” with Dr. Ian Graham (Nov. 16th and Dec. 12th, 2022) |

These events have passed – view the recordings in our webinar archives.

| Events, Other | November 9, 2022 | events other | cekter knowledge-translation kt-academy psychiatric-rehabilitation webinar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Peer Support Specialist Workforce: Where have we been and where are we going? | Brief History

The CPR was an ally in the advocacy work of movement activists. Those early days focused on “consumer” voice and participation in mental health policy and practice, under the motto, “Nothing About Us Without Us.” Simultaneously, the power of peer relationships in peoples’ healing and recovery, called “peer support” today, was highlighted in Judi Chamberlin’s seminal book, “On Our Own,” and incorporated into the values and practices of psychiatric rehabilitation. Prior to Medicaid funding, some headway was made with the creation of a “consumer liaison” role in some states, and other nominal “consumer” roles in services. However, even the willing were hindered by the usual issue, i.e., funding. The “Certified Peer Support Specialist” In 1999, the Georgia Mental Health Consumer Network gained Medicaid approval (i.e. funding) for a new role – “Certified Peer Specialist” By 2005, states across the country began to follow Georgia’s lead and when the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) not only endorsed peer support as an emerging best practice in 2007, but encouraged states to utilize peer support,[1] the flood gates opened. By 2016, there were at least 25,317 peer support specialists in the US.[2] The rare “consumer” role of the 1990’s has now become a common role throughout behavioral health.[3] It should be a time to celebrate all that has been accomplished, right? Well, maybe….and maybe not. Unintended Consequences

The word “peer” in “Certified Peer Specialist” is intentional and signifies the mutual relationship between two people with shared experience that was the hallmark of peer relationships in the c/s/x movement communities. The intent of the “Certified Peer Specialist” role was simply to bring this impactful community role into services to create access for people who couldn’t access and get the benefit of peer-run agencies in the community. Peer support is meant to offer the comfort of “been there, done that” and the hope of “…and I’m not there now.” The peerness of the relationship – that is, no one holds power over the other – is what separates peer support from other roles and is often what opens the door to connection and trust. There are many more professionals working in mental health, sharing their lived experience.. However, with or without lived experience, the traditional workforce still holds power over people in services. An authentic peer specialist does not. They are meant to be “in but not of” the system as a new and different type of provider unconnected to the culture of the medical model. With hindsight, it’s clear that implementation of the role skipped the vital steps of preparing agencies and their staff for the influx of Certified Peer Specialists, resulting in a clash of cultures. (Byrne et al., 2019. “The emphasis was initially on bringing the values and principles of peer-developed peer support into paid peer staff roles, but the ability to keep the focus on these values [is]often compromised by clinicians and administrators who do not understand or support the principles (Jones et al, 2020; Stastny & Brown, 2013). Inevitably, the role has become co-opted, with “mutuality”, the first critical component of peer support to be set on a shelf to get dusty and forgotten. Similarly, “relationship,” is often sacrificed as peer support work often prioritizes the “deliverable” task at the expense of the relationship. Here’s how one peer provider described their role, “They changed the scope of what peer support really is… Now there’s that movement that kind of makes people, what I like to refer to as mini clinicians. Minus the white coat, they’ve got their clipboard and they’re taking notes, ‘How does that make you feel?’” (Adams, W. 2020)[4] Changing the Tide The Center is dedicated to preserving the “peerness” of peer support specialists. The Recovery Education Center, provides recovery/wellness education classes, many facilitated by people with lived experience who also provide one-to-one support to students in their classes. Many former students go on to become facilitators and peer support specialists, themselves. Research projects, in addition to having people with lived experience involved in research project design have also focused on delivery of authentic peer support in services. One example is the Vocational Peer Support (VPS) training that was developed and researched at the Center. Another is a current study developing a way of providing Executive Coaching for peer supporters. The Center’s Post-Doctoral Fellows have also focused on authentic peer support. The most recent example of this is Wallis Adams who, partnering with the National Association of Peer Supporters (NAPS) performed two studies: The Impact of Covid on Peer Support Specialists and Barriers and Facilitators of Implementing Peer Support Services for Criminal Justice-Involved Individuals. Continuing this tradition, the Center will be dedicating a series of webinars ( “Ask Me Anything”) on the peer support specialist workforce in 2023. Announcements will be made when registration is open for these. The role of people with lived experience, as well as the peer support workforce, will continue to be at the heart of research, training and services at the Center. [1] CMS Letter dated August 8, 2007 (SMDL #07-011). [2] Wolf, J. (2018). National trends in peer specialist certification. Psychiatric Services 69 (10), 1049. This number does not include thousands of non-certified peer support workers as well as those employed in forensic, youth, parent partners, substance use and other behavioral, primary and integrated health settings as well as serving specific population groups. [3] Cronise, R., Teixeira, C., Rogers, E. S., & Harrington, S.(2016) The peer support workforce: Results of a national survey., Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 39(3), 211-221. [4] Adams, W. 2020. Unintended Consequences of Institutionalizing Peer Support Work in Mental Healthcare. Social Science & Medicine, 262.

Notice: The contents of this post were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RTEM0004). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this post do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. | Articles, Employment | September 2, 2022 | articles employment | peer-support psychiatric-rehabilitation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| What is Psychiatric Rehabilitation? | Welcome to the Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation official blog! For our inaugural article, we thought we would tackle a basic question that the Center has contributed to answering over the years, i.e. What exactly is “psychiatric rehabilitation”?

The Deinstitutionalization MovementLet’s begin by reviewing one of the most important factors in the historical context of the development of psychiatric rehabilitation: The deinstitutionalization movement in the United States and abroad. Deinstitutionalization as a movement was motivated by an understanding that the typical incarceration of people with mental health conditions on locked wards in long-stay hospitals, was not necessary. We learned that it was possible to design effective services, in the least restrictive setting, while helping people to keep their personal dignity and self-determination. Following the release of the anti-psychotic, Thorazine and numerous other psychiatric medications, the in-patient census was reduced from approximately 560,000 people in psychiatric institutions in 1955, to approximately 70,000 by 1994. Even though President Kennedy’s Community Mental Health Centers Act of 1963 achieved a breakthrough in developing community services, more than 90% of people – many who spent virtually their entire lives in institutionalized psychiatric settings – moved into communities by the mid 1990’s, often still without sufficient support services in place.

Marianne Farkas, Director of the Training, Dissemination, and Technical Assistance Division here at the Center, recalls doing a project at an in-patient institution in Maine, helping them to improve their deinstitutionalization efforts. She encountered residents, such as 58-year-old Betty, who were leery of those efforts. Betty had lived in the institution for more than 25 years and was not eager to leave. It is not terribly difficult to understand such an attitude. Betty watched other residents separated from their routines, caretakers, and friends as they were simply given a prescription for their medication and ushered out the door. These people were unprepared to choose or pursue valued roles in the community. In many cases, people had been institutionalized for so long that mere identification of a community role – something that requires self-knowledge about one’s values and possible options – was a seemingly monumental task. Marianne’s project focused on the facilitation of services to help Betty and others like her, to live in the community, rather than just get placed there, using psychiatric rehabilitation techniques.

Psychiatric Rehabilitation: A Response to the Deinstitutionalization MovementAs the Center’s founder, Bill Anthony once said “If deinstitutionalization was to give freedom to people with psychiatric disabilities, psychiatric rehabilitation would create the space and structure for a meaningful life within that freedom.” So, what is psychiatric rehabilitation (PR)? The name can be a misleading. It does not necessarily imply the involvement of a psychiatrist or really of any form of psychiatry. Rather, the term ‘psychiatric’ describes the disability that rehabilitation activities address, just as the term “physical’ rehabilitation describes the kind of condition (i.e., physical disabilities) addressed. The term ‘rehabilitation’ indicates that the activities are concerned with the performance of a specific role (e.g., worker, student, parent) in specific environments. PR helps people consider, research, choose and achieve a major role in a specific environment, that is personally meaningful. These “role goals” may involve, for example, working part-time as cashier at McDonald’s or completing a Community College certificate in Addictions Counseling. The Center’s materials can help providers learn how to use PR techniques to facilitate a person identifying such goals ( e.g., rehabilitation readiness, setting an overall rehabilitation goal).

Psychiatric Rehabilitation vs. Physical RehabilitationDifferent “role goals” make unique demands on an individual in order to succeed, regardless of the source of their challenges. Rehabilitation, of any kind, aims to restore functioning in people’s lives by teaching skills and modifying the environment in order to maximize independence. For example, being able to transfer from bed-to-chair might be a skill necessary for an individual with a spinal cord injury. Railings or other supports might, together with this skill, help that person to perform the tasks needed to succeed in their role as parent at home. In a work role, skills such as accepting negative feedback from a supervisor or improving job-specific skills might be critical for the individual. However, beyond skills, that same individual might need their workspace to conform to wheelchair accessibility guidelines, to support their ability to succeed at work. This combination of skill and environmental support allows the individual, regardless of their type of disability, to perform well in their preferred valued roles.

Psychiatric Rehabilitation Techniques Developed at the CenterTechniques developed at the Center transfer these ideas from the realm of physical rehabilitation to psychiatric services (e.g.. PR Functional Assessment and Skill Teaching) and help people in mental health recovery figure out and develop the skills they need for their specific selected role goal. Young adults who live with mental health and/or substance use conditions who’ve experienced an interruption to their pursuit of higher education, develop critical skills and supports in the NITEO program, one of many College Mental Health Education Programs at the Center. NITEO supports young adults prepare for a successful re-entry to college. Beyond college, people who want to consider or succeed in work may struggle specifically with cognitive difficulties. Participating in Thinking Skills for Work, developed by the Center’s faculty (Susan McGurk and Kim Mueser), has been demonstrated to improve employment outcomes when TSW is delivered together with Supported Employment. Thinking Skills for Work (TSW) trains people in core cognitive skills important to the work goal they may have (e.g., paying attention, planning, organizing etc.), as well as self-management skills. For example, one TSW self-management strategy is the use of a “memory spot”, a place selected to regularly keep important personal items like keys or a wallet, to address problems associated with memory problems that interfere with work functioning.

The Importance of the EnvironmentPR is about the person in the environment. I can be very good at my job and not doing terrifically as a parent. Beyond my parenting skills, I might need environmental modifications and supports. I may need a babysitter to cover time between the end of the school day and when I get home from work. No matter how skilled I am, that support is critical to my success. Most of us are dependent on some support to succeed in the many roles we juggle in our lives. For example, common supports like public transportation, an alarm set to wake up, having a doctor, friends or recreational facilities can help the average person to succeed, including a person in mental health recovery. The Center’s focus on the importance of such support and strategies to modify the environment-rather than only focusing on changing the person, was a breakthrough in the realm of psychiatric services. New Center interventions such as Bridging Community Gaps, using Photovoice, help people make better use of what the community has to offer. Interventions such as PR case management help people to develop and link with needed supports.

The belief that every human being has the right to live a personally defined, meaningful life is a cornerstone of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. Its processes are based on a belief in our common humanity, regardless of the challenges we must face. PR recognizes the importance of supporting people with psychiatric disabilities in identifying and thriving in their preferred valued role. Consistent with the broader field of rehabilitation science, PR accomplishes its aims with a combination of skill development and environmental accommodation and may encompass a wide range of modalities, depending on the specific roles selected by the person. To learn more about the PR process and approach, check out our Primer on the Psychiatric Rehabilitation Process or, for a deeper dive, consider our textbook: Psychiatric Rehabilitation, Second Edition. We hope you enjoyed our first post! Please let us know what you think in the comments section, below, and subscribe in the sidebar on the right!

Notice: The contents of this post were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RTEM0004). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this post do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. | Articles, Employment | March 11, 2022 | articles employment | deinstitutionalization psychiatric-rehabilitation serious-mental-illness | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Our First Blog Post is Coming Soon… Stay Tuned! |

| Events | February 25, 2022 | events |

![MAKING SENSE OF S.I.L.V.E.R RESEARCH. Making Sense of S.I.L.V.E.R.* Research is a webinar series, designed for everyone! It presents a recent, relevant research study in clear, understandable language, with time for you to ask questions. *Supporting Individuals to Live as Vibrant Elders in Recovery. Presentation: 'Promoting Recovery Among Older Adults with Serious Mental Health Conditions: Strategies for Implementing Psychosocial Interventions in Community Mental Health Settings' This presentation will discuss the needs of older adults who have serious mental health issues and the way that we're working to help them in their communities. We'll discuss a program we've developed to improve their health and social skills. We'll also look at the different ways we've tried to make this program work, what's been successful, and what hasn't. We'll talk about how the organizations involved and the resources in the community affect how well the program works and whether it can keep going in the long run. Nathaniel A. Dell, PhD, a licensed clinical social worker, is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, MO. His research interests include evaluating evidence-based practices for people with serious mental illnesses & co-occurring disorders; promoting the uptake of evidence-based, recovery-oriented psychosocial interventions; leveraging big data & data science approaches to identify the behavioral health needs of hidden and hard-to-reach populations, such as people experiencing homelessness. Join Us: April 11th, 2024, 12:00 PM EST Register Here: [URL provided]. This event is supported by funding from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research. NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this project do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government](https://cpr.bu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SILVER_MSR_4-11-2024.png)

![S.I.L.V.E.R. Ask Me Anything. Join us on: Friday, March 22nd, 1:00 – 2:00 PM EST. Forging a Resilient Alliance to Promote Connectedness Among Older Adults with a Psychiatric Disability with guest experts Dr. Laura Leone, Lyn Legere, and Karen Gross. You’re invited to a discussion with an expert about an interesting topic related to 'Supporting Individuals to Live as Vibrant Elders in Recovery' or S.I.L.V.E.R. This free event is not a presentation, but rather an opportunity for you to have an interactive question & answer session. Zoom Registration: [URL provided]. Laura Leone, DSW, MSSW, LMSW is a consultant for the National Council for Mental Wellbeing. She has worked in the behavioral and integrated health field providing organizational leadership and direct services across the lifespan, including for older adults. Having published, trained, and consulted nationally, Dr. Leone has extensive subject matter expertise in health and wellness, including in Aging with Mental Health challenges. Lyn Legere has lived a life in many chapters, including living as a 'mental patient' and building a life in recovery. Now, at 70, she is in a new chapter, navigating life that, in part, includes consequences of the past and recovery tools to thrive. Karen Gross has been an advocate and caregiver for an older sibling who experiences severe mental health challenges. Now that her sibling is 72, she wants more help for his care but is very weary of governmental services that might diminish the quality of his life in exchange for what a system deems mandatory. The content of this presentation was funded by the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR), ACL, HHS, and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). This content does not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.](https://cpr.bu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/silver_AMA_3-22-24.png)

![MAKING SENSE OF EMPLOYMENT RESEARCH. Ever wonder what researchers are finding out about employment for people with mental illnesses/mental health conditions? The Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation is pleased to present 'Making Sense of Employment Research', a webinar series designed to discuss a recent published research study, in a clear and relevant way, even for those who know little or nothing about research. Presentation: 'Virtual Reality Job Interview Training: An Enhancement to IPS Supported Employment for Adults with Serious Mental Illness' Dr. Smith's presentation will focus on his program of research that develops and evaluates virtual reality job interview training as an enhancement to existing employment services, in particular, the individual placement and support model of supported employment. Join us: Matthew J. Smith, PhD, is a Professor of Social Work at the University of Michigan and a Licensed Clinical Social Worker. Smith is the director of the NIH-Funded Level Up: Employment Skills Simulation Lab. The mission of his lab is to develop and evaluate technology-based interventions to help obtain and sustain employment for people from marginalized and underserved communities. March 31st, 2023 12:00 pm EST Register HERE Or go to: [URL provided] BOSTON UNIVERSITY | NIDILRR This event is supported by funding from The National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RT504). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this project do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. https://bostonu.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_uDmECYhVRU-UcC4TTYvrxA](https://cpr.bu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/mser.png)

The Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation (CPR) at Boston University has partnered with the voices of those with lived experience from its’ earliest days – that is, the voices of those who would eventually populate the peer support specialist workforce. Luminaries in the field such as Pat Deegan, Judi Chamberlin and

The Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation (CPR) at Boston University has partnered with the voices of those with lived experience from its’ earliest days – that is, the voices of those who would eventually populate the peer support specialist workforce. Luminaries in the field such as Pat Deegan, Judi Chamberlin and